January 16, 2026

Introduction

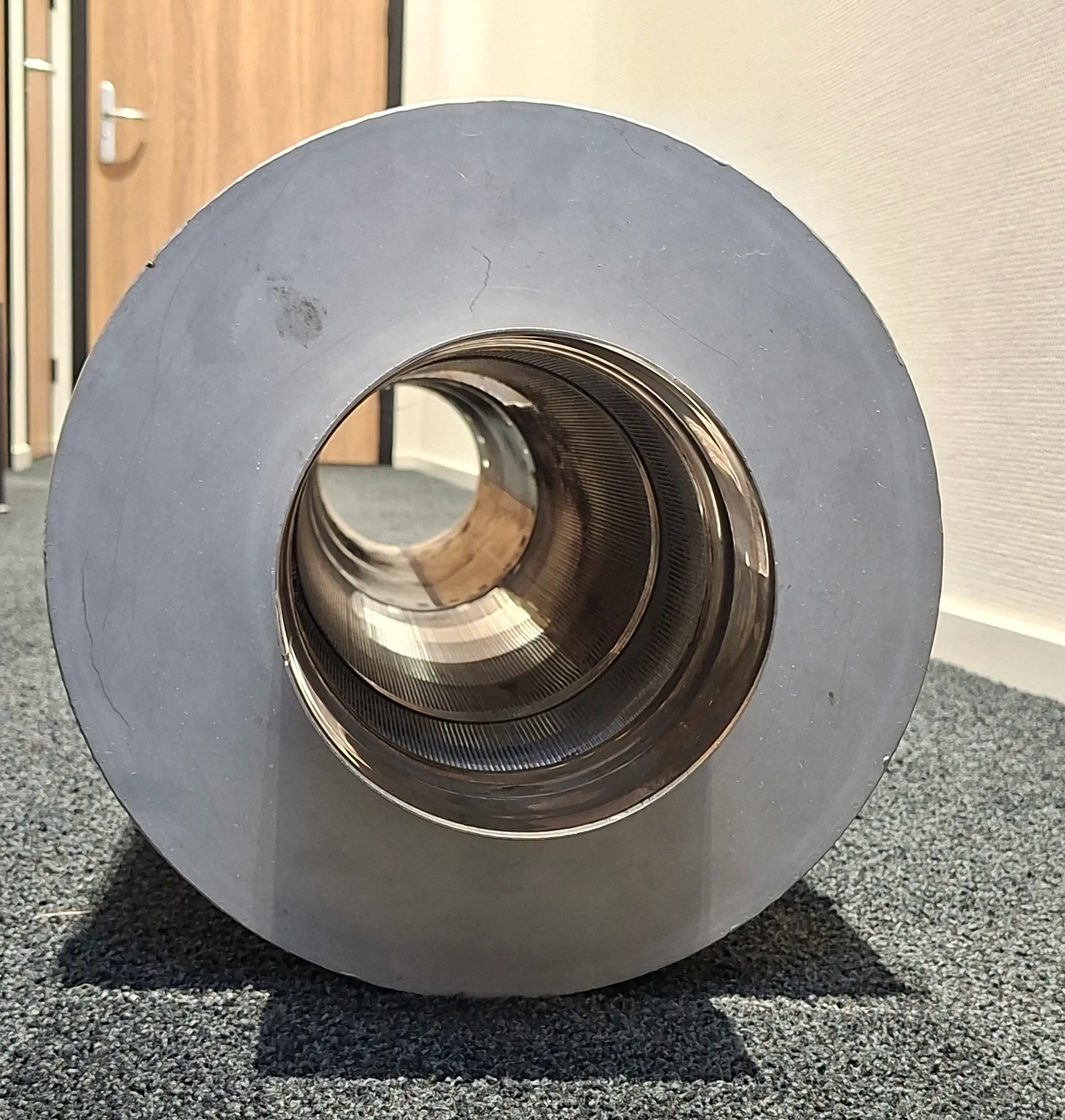

In the hallway of our office, we store a reactive silencer. It is a good conversation starter as people wonder what it is. In this blog, we will explain how the it works and why it is so good in specific applications. To be precise, we will describe a straight through duct silencer with side branch resonators. Such silencers find application in engine air intakes and performance exhausts. This specific one has been used in a wood fired burner.

Reactive silencer in the hallway of our office

... silencer

Sound can be anywhere. Different geometries require different approaches. In this case, we talk about sound that propagates through a duct. An example is the exhaust of a car. The sound all is concentrated in a small duct.

Before we dive into the working mechanism, we first have to establish what exactly is sound in a duct. Sound is pressure fluctuations, superimposed on the mean pressure. These are accompanied by velocity fluctuations. Any mean flow velocity, which generally is the purpose of a duct, can be ignored for now: we only consider acoustics. Furthermore, we only consider traveling waves and assume that the duct diameter is small, compared to the wavelength, so all waves are plane waves. For a plane progressive wave, the frequency domain ratio between pressure $p$ (Pa) and velocity $u$ (m/s) fluctuations is the specific characteristic acoustic impedance $z_c$ (mks Rayl):

$$ z_c = \frac{p}{u} $$

which is a property of the gas inside the duct. It happens to be around 415 mks Rayl for air at room temperature. That means that a propagating sound wave with a pressure amplitude of 415 Pa is accompanied by a velocity amplitude of 1 m/s.

So how can we add something to the duct, to prevent such fluctuations from reaching the other end? Let's try a vacuum cleaner to suck up the velocity fluctuations! The equation stated above implies that the pressure fluctuations will also be gone.

A vacuum cleaner removes unwanted sound

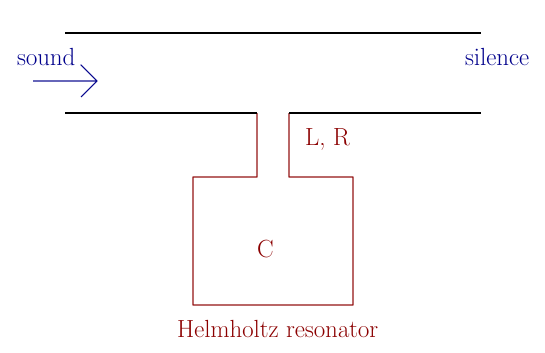

A more scientific explanation can be given with a lumped element model. Our reactive silencer is a Helmholtz resonator:

A Helmholtz resonator, attached to a duct as a side branch resonator

This is an $RCL$ network, in which the C describes the compliance of the air volume, L the acoustic mass of the neck and R any flow resistance located at the neck. The neck is formed by the hole pattern, while the air volume is the space in-between the perforated tube and outer shell:

Close-up showing the hole pattern near the top of a chamber, which forms the neck (L, R) of the Helmholtz resonator. The cavity (C) is formed by the air volume between the perforated tube and outer shell.

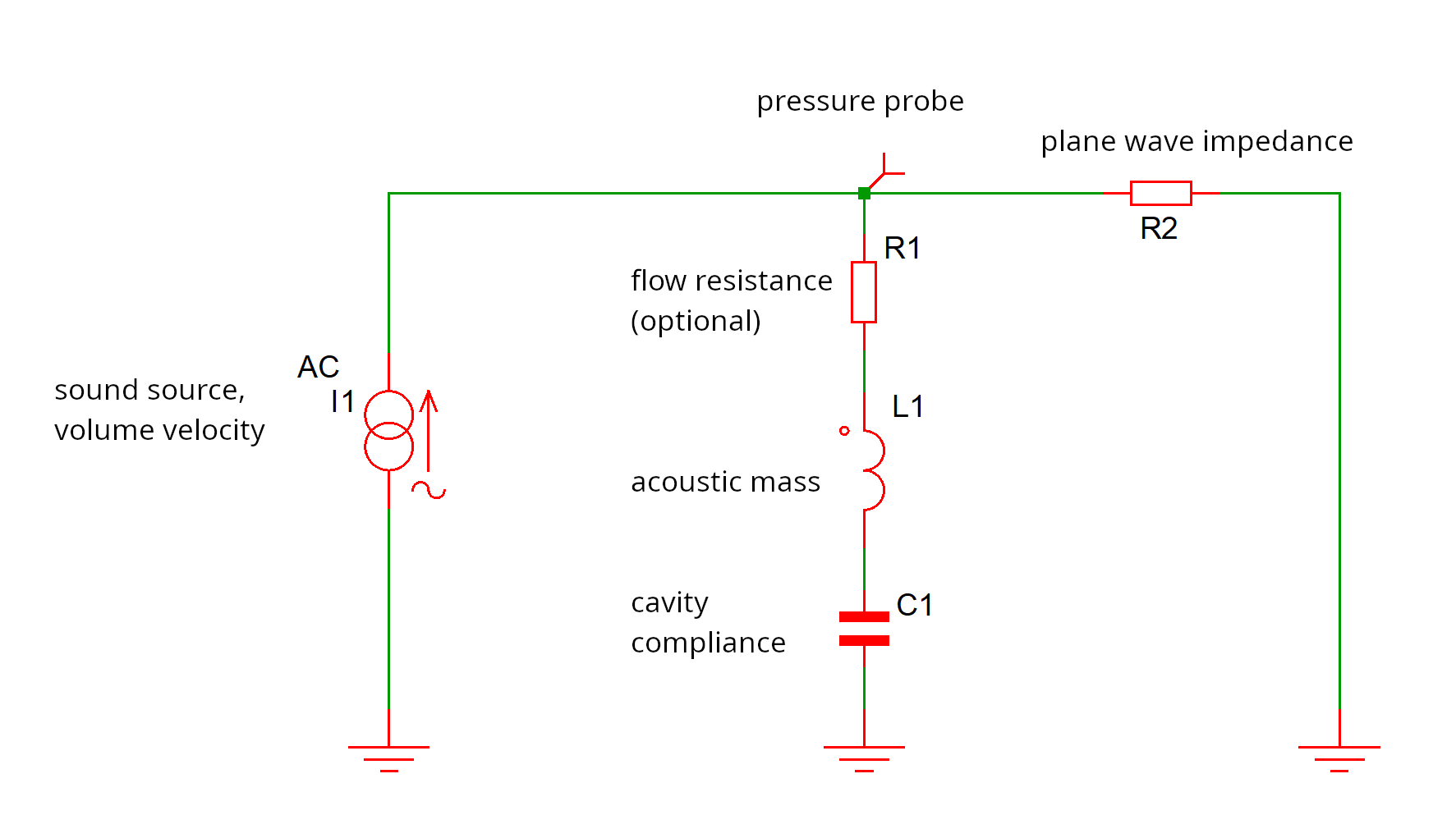

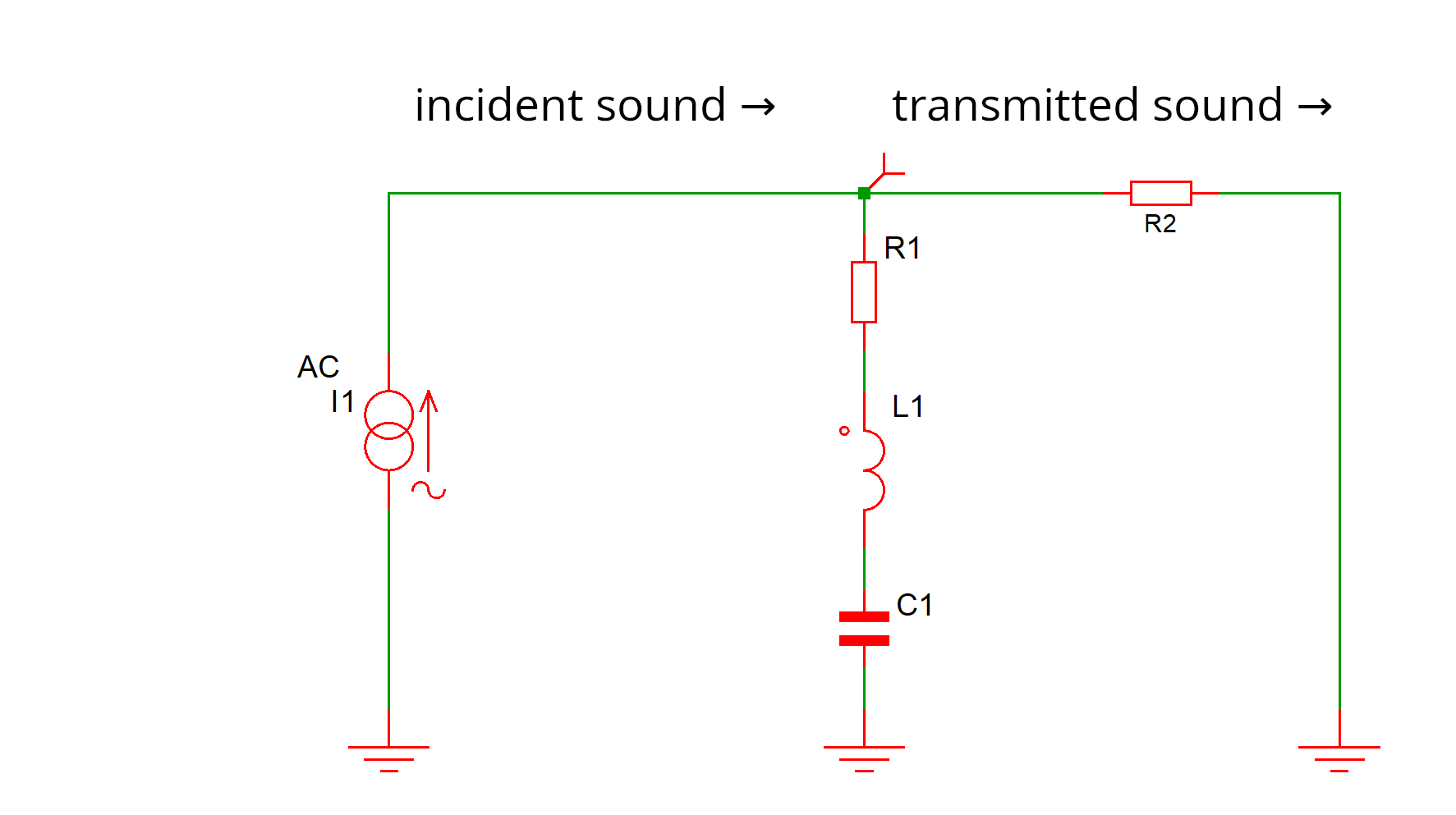

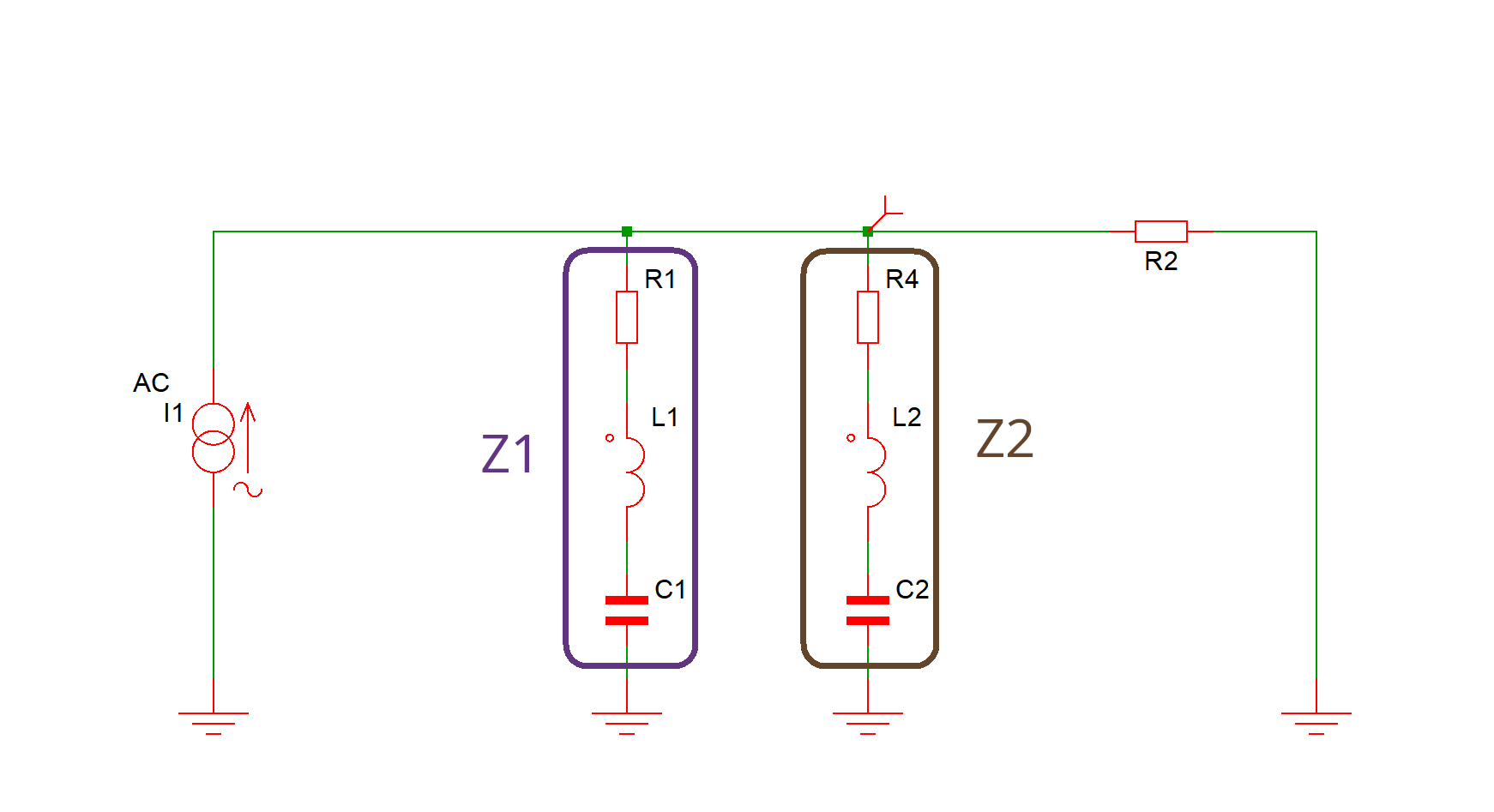

As an electrical circuit, the $RCL$ network looks like this:

Lumped element model of a Helmholtz resonator, attached to a duct as a side branch resonator

The silencer has been added to a duct and is drawn as the $RCL$ network $R_1$, $C_1$, $L_1$. On the left, there is a piece of duct with incoming sound, modeled as a current (volume velocity) source $I_1$. On the right, there is a piece of duct which we want to be quiet, which has input impedance $R_2$.1 The voltage (acoustic pressure) is probed at the T junction. Simulating a duct with incoming sound as a current source and the other duct as a plain resistor is incorrect, but it will do here, to explain the working mechanism.

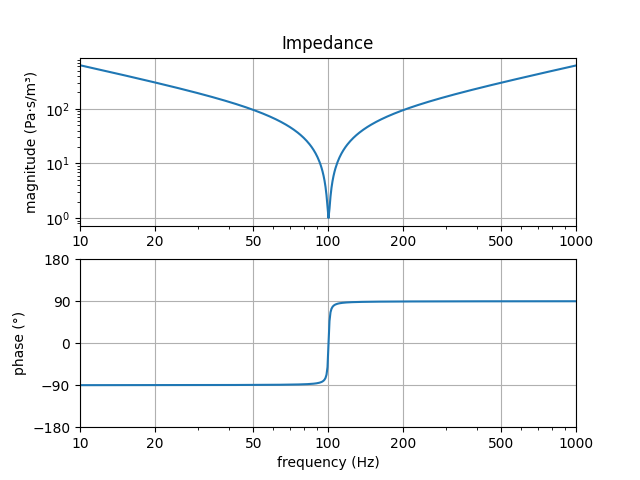

An $RCL$ network has the following impedance graph:

Impedance of a series RCL network

At one specific resonance frequency, the impedance is really low. The reactances of the compliance and mass are equal in magnitude but opposite in sign and cancel. What remains is the resistance, which generally is low.

Returning to the lumped element model, the implication is that the incoming velocity fluctuations are shorted to ground by the silencer. That means that the pressure fluctuations at the T node are zero. Therefore, no sound is passed to the exit duct. The result is silence.

Transmission loss

By comparing the transmitted and incident sound, we can determine how much 'transmission' is 'lost' due to the silencer.

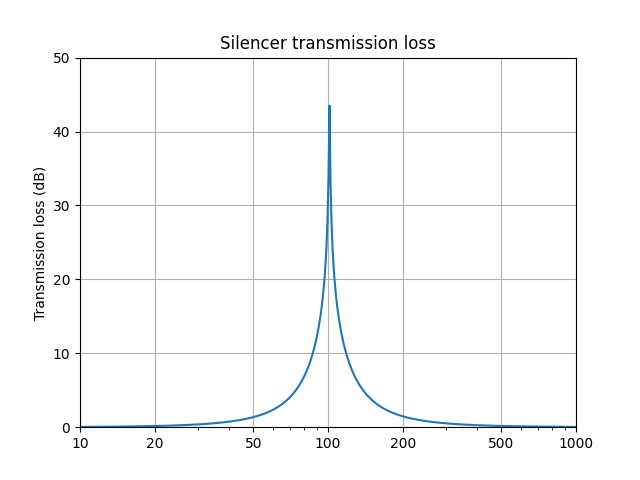

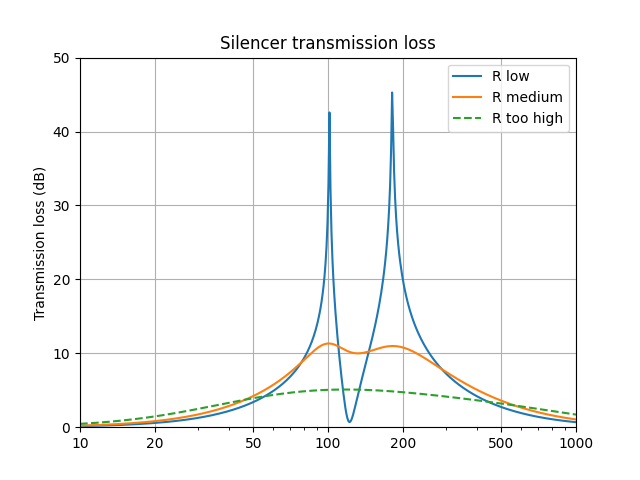

As a function of frequency, we get the following transmission loss. A high value means that the sound is attenuated well. The following example suppresses sound at 100 Hz:

Example of a transmission loss graph

What makes them so good

A traditional fibrous-filled silencer has to be physically large, in order to work at low frequencies. One advantage of reactive silencers is that they can work at low frequencies, even if their dimensions have to be kept small. The resonance frequency of the silencer is given by:

$$ f = \frac{1}{2\pi\sqrt{L C}}$$

and as L can be chosen almost freely, it can be used to tune f to a low value.

A second advantage becomes apparent when you attempt to see trought the silencer:

A straight-through silencer offers little flow resistance

You just can. There is no obstruction to the airflow at all, except for some small holes in the duct wall. That means that such a silencer does not pose a significant flow resistance to anything flowing through it.

A third advantage is that the silencer is not filled with a fibrous material. Such fibers are prone to decay after years of use or can be blown into air that should remain clean.

Widen the peak, and you'll broaden your opportunities.

The silencer we just discussed has one major flaw: it only works at one frequency. That will work if the noise contains a fixed tonal component, like a fan which always spins at the same rotational frequency. It even works well and only requires minimal physical dimensions. However, most sound sources are broadband or can run at different rotational frequencies. Attenuation is needed across a wider frequency range. How do we widen the peak?

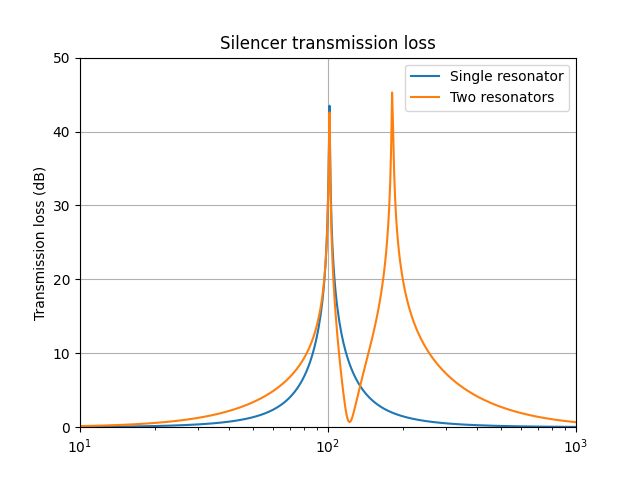

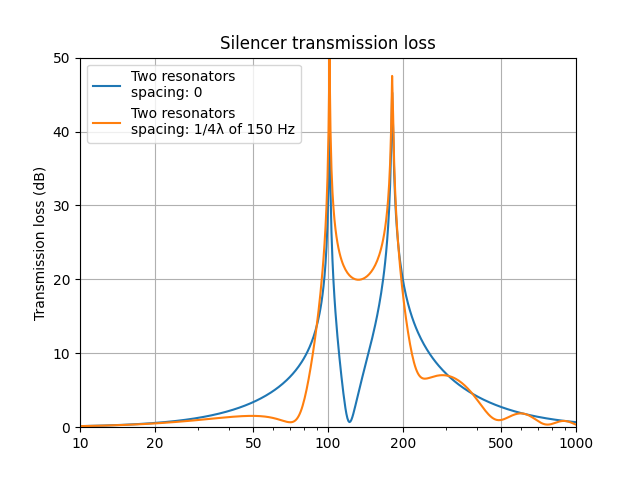

An obvious method is to parallel multiple Helmholz resonators into one big silencer, each tuned to a different frequency.

Adding a second resonator adds a second peak in the transmission loss

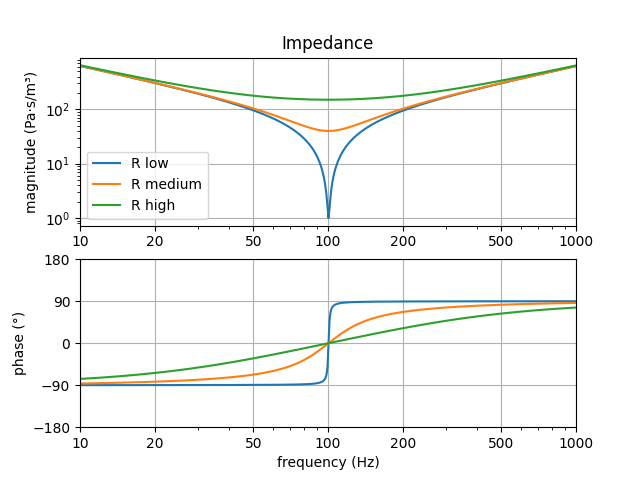

That does not seem to work as planned. There is an extra peak in the transmission loss, but in-between the peaks, the attenuation has gone down. Not good. It happens because the phase of the RCL network:

Impedance of a series RCL network: effect of R

For a low value of R, the impedance $Z$ of an RCL network is -90 degrees on the left of the peak and +90 on the right. If the first resonator has impedance $Z_1$ and the second has $Z_2$, then in-between the peaks, $Z_1$ and $Z_2$ have opposite phases:

Lumped element model of two Helmholtz resonators

Parallelling two equal and opposite impedances creates an infinite resistor, which is not the low value we need. The two resonators fight each other. The solution is to add a controlled amount of resistance, which moves the phase of each branch closer to 0 degrees. Check out the effect in this figure:

Adding flow resistance to the Helmholtz resonators nicely fills in the gap between the peaks

A little damping nicely broadens the frequency range, across which the transmission loss remains above a useful 10 dB. The resistance should be tuned carefully, as too much stops the resonators from resonating.

All roads lead to Rome

But wait, there is another way to obtain attanuation over a wider frequency range. Instead of placing both resonators at the same position, it is possible to spread them apart. It is another solution to solve that $Z_1$ and $Z_2$ have opposite phases. With a spacing of one-fourth of the wavelength of the frequency right in-between the peaks, the gap is nicely taken care of:

Spacing the resonators away from each other is another tool to fill in the gap between the peaks

In practice, we use a combination of the techniques listed above.

Return to sender

Even in the case of R = 0, the silencer still works. The L and C cannot dissipate energy, so where did the sound go? From the ducts perspective, the one with incoming sound, a silencer presents a sudden impedance jump to zero. Such a jump means that the sound is reflected back to where it came from. Incoming sound power is returned to the sender, just like unwanted mail.

Wrapping up

We have learned how a reactive silencer works and why it can be a good option in some applications. I'd like to finish this blog with a quote: "In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends." (Martin Luther King, Jr.) That applies to exhaust notes as well.

-

In the simple case that this duct somehow accepts all incoming sound and reflects nothing back, the resistance is the plane wave impedance, which is the specific acoustic impedance divided by the ducts cross-sectional area. ↩